by Bryan Furuness

Imagine me, a rumpled professor, standing in the end zone of a football field. In the other end zone is a student. “Come over here!” I call. The student takes a few steps out to her own five-yard line.

“Here?” she says.

“No, here!” I say, pointing down at my own end zone.

She takes one more step and smiles. “Oh, here.”

I lie down on the grass and go to sleep for a million years.

For years, this was pretty much how I taught revision. I asked students to make substantial changes. I gave them suggestions and strategies. Why didn’t it work? Why was it so hard to get them to go beyond tinkering and polishing?

It wasn’t until I read “Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers” by Nancy Sommers, founder of the Harvard Writing Project, that I finally understood. My students’ tentative approach to revision didn’t come from a place of laziness or caution. It wasn’t due to a lack of skill, either. It was firmly rooted in their philosophy of writing. What you think about writing, it turns out, informs the way you rewrite.

Thinking about Writing

Here’s a typical student view of the relationship between ideas and writing: I already have my idea. Writing is a way of communicating that idea. My job is to find the right words.

An experienced writer, on the other hand, is more likely to think: I have an idea, but I know that it’s not fully formed. Writing is a way of discovering what I really think, and then developing and deepening that idea. Writing is a way of making meaning.

To put it another way, experienced practitioners write to figure out what they mean to say, while students think they know what they want to say at the start of a project.

Thinking about Rewriting

If you think that your idea is fully-formed, of course you will be reluctant to make any big changes. Big changes might alter your idea—and why would you want to do that? Rather, you’d try to make little changes to communicate your initial idea more clearly.

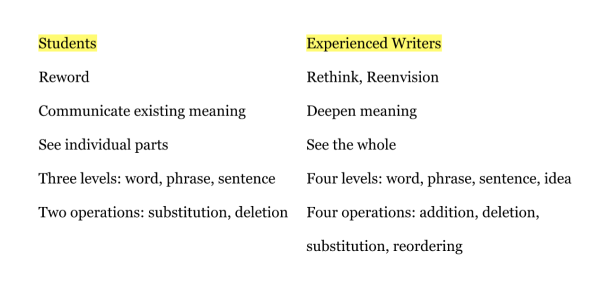

Which is exactly what Sommers found. When she asked students to define revision, they talked about reading through a draft and replacing words and phrases. For one student, revising meant “using better words and eliminating words that are not needed. I go over and change words around.”

For the students in Sommers’s study, revising=rewording (I’m painting with a broad brush here, I know. But I can think of few exceptions. Sommers is really onto something.) But when Sommers asked for a definition of revision from a cadre of experienced writers—journalists, editors, academics—she found that they were breaking out the earth-moving equipment. For one experienced writer, revising meant “taking apart what I have written and putting it back together again . . . I find out which ideas can be developed and which should be dropped.” Ideas, not individual words. Considering the whole, not little parts in isolation.

From the Philosophical to the Practical

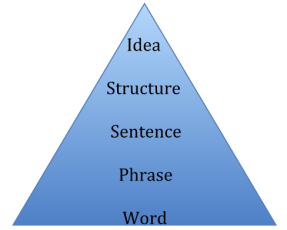

Sommers identifies four levels of change that can happen during revision: word, phrase, sentence, idea. I propose adding a fifth level: structure, or architecture. This would come into play when you’re working with blocks bigger than sentences—paragraphs, scenes, sections, chapters—or changing the form entirely. Here, then, are my revised levels, with the lowest order on the bottom and the highest order on top.

While most students get stuck on the lower levels, experienced writers can access all five levels, though they tend to start with the highest level. Experienced writers are like hawks, soaring over a manuscript to view the whole hunting ground, but able to swoop down to a line, a single word. Novice writers are more like dachshunds, sniffing along the lines, seeing each little part without much sense of how it relates to the whole.

Okay, Furunicorn, experienced writers are magical hawk-gods who can see in five dimensions. But what do they actually do on these levels?

Sommers points to four revising moves: reordering, addition, deletion, and substitution. Experienced writers use all four moves. Students tend to stick to the smaller moves of substitution and deletion, usually on the word or phrase level. (Do you see how this fits with the mindset of writing-as-communication, revising-as-rewording? This is why my old method of telling students to make big changes never worked. Everything I said ran counter to their underlying philosophy—and I never directly addressed that philosophy, much less tried to change it.)

Let’s recap. Below are the big differences between student writers and adult experienced writers, as discovered by Sommers:

Which brings us, at last, to the big question: How can we help writers migrate from the left column to the right column?

Adjusting their understanding of revision wouldn’t be a bad start. How long would it take to make such a fundamental shift? Try eight minutes.

A New Working Definition of Revision

In 1990, researchers David L. Wallace and John R. Hayes conducted a study on the “impact of task definition on students’ revising strategies.” As we saw in Sommers’s study, students typically define revision as a local task—playing with little parts instead of the whole, tinkering with words instead of ideas or architecture—but what would happen if students thought of revision as a global, holistic task?

To find out, the researchers gathered two groups of first-year college students. Both groups were given an identical essay to revise, but the treatment group was given eight minutes of instruction on how to revise globally, while the control group was just told to “make the essay better.”

Eight minutes! It’s hardly any time at all. You probably spent eight minutes settling down to read this essay. In this study, an instructor put that time to good use by showing the treatment group a comparison between revisions made by an expert writer and by a novice writer. What were the differences? Nothing that would surprise Sommers:

Did the instruction pay off? According to two judges who read the revisions from both groups, the students who got the instruction “were able to produce a significant increase in global revision and in revision quality.”

Surprisingly, the researchers don’t take credit for teaching these students any new skills. Rather, they argue that the students already had these revision skills. What allowed the students to access those skills? A new vision of revision as a global task.

This is all very impressive, and it makes me wonder: What would happen if they had spent more than eight minutes teaching revision? What would happen if, instead of starting with the task definition of revision, they had gone all the way back to square one and addressed the students’ philosophy of writing?

Like you did in this essay, Furuncle?

YOU GOT ME. I confess: This essay is my sneaky way of shifting your mindset and practice. Wallace & Hayes might have wanted to adjust your definition of revision, but I want to go deeper, all the way to the root. I want you to think of writing as discovery, and revision as deeper discovery. I want you to see revision as the continual process of looping back to figure out what you mean, a “repeated process of beginning again,” as Sommers puts it in a different article.

By the way, the research in this essay might focus on composition classes, but the findings translate to any kind of writing, and any kind of writer. The creative writer who is married to his “intent for a story” and the high school sophomore riffling through her thesaurus to find the right words to “get her idea across” about capital punishment are both laboring under the notion that their ideas are already fully-formed. Both could benefit from a shift in philosophy and process. Such a shift will not only allow them to transform their early drafts; it would transform them as writers. That’s my hope, my vision for all of us: To become better, truer, more powerful writers; to let this process rewrite us.

Bryan Furuness is the author of The Lost Episodes of Revie Bryson, a novel. He teaches at Butler University, where his office currently has no heat. He doesn’t mind, because this gives him an excuse to wear fingerless gloves and pretend to be Bob Cratchit.

Bryan Furuness is the author of The Lost Episodes of Revie Bryson, a novel. He teaches at Butler University, where his office currently has no heat. He doesn’t mind, because this gives him an excuse to wear fingerless gloves and pretend to be Bob Cratchit.